In this latest blog post – or rather series of three posts – we thought we’d try something a little different. Whilst most of our posts address aspects of the health and wellbeing space that Health Diagnostics work in, key to that work is the amazing team of people that make up our organisation. Over the coming months, we thought we’d tell some of the stories of that amazing team: their personal journeys, what makes them tick as individuals, and the work they do day-to-day at Health Diagnostics.

Whilst, in future blog posts, you can look forward to hearing about a handful of the people that head-up some of Health Diagnostics’ various departments, in this first ‘people post’, we wanted to focus on Ashley Terry – Project Manager and Admin Support at Health Diagnostics – whose deeply moving and extraordinarily inspiring story is quite unlike that of any other member of our team.

Ash’s story – an astonishing account of fortitude, determination, and resilience – speaks directly to the deep gratitude that so many in our country feel for the NHS. The work that Ash and the rest of the team at Health Diagnostics undertake in driving quality and innovation in prevention is central to supporting our health service into the future. Ash’s poignant personal account of his experience is a reminder to us all of why, in our own way, we do what we do: to support people to change their lives for good and to live healthier for longer. In our shared view, delivering on this ambition will, over the coming years, be key to determining whether the NHS is able to focus less on treating preventable illness and more on providing the exceptional standard of specialist care that it remains a world-leader in.

Over to Ash…

My Unexpected Detour and Finding My Feet Again

In 2020, aged 24, I was an optimistic postgraduate focused on climbing the corporate ladder. Life, however, had a starkly different path in store for me. Over a short period, alarming symptoms emerged, leading to a diagnosis I never anticipated: a pontine glioma. This malignant brain tumour originates in the pons, the brainstem’s vital hub responsible for regulating essential functions like breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure, to name a few. It is often accompanied by a poor prognosis due to its location and rapid growth. For the past five years, I’ve navigated life with this tumour, and I want to share my experiences – the hurdles, the struggles, and the unwavering belief that even in the darkest times, positives can be found.

The First Signals: A Change in Perspective

The initial signs appeared in the spring of 2020, with my vision being the first to change. Working from home during the COVID-19 lockdown, I distinctly remember looking into the garden one sunny afternoon and seeing three dogs when in actuality, I knew there were two. This progressively got more intrusive and became worse in the following months. Alongside my double vision came bouts of dizziness, an uncharacteristic clumsiness that had me tripping and bumping into things, slurred speech and difficulty swallowing, which eventually hampered my ability to do my job. Nausea, fatigue (especially noticeable when working from home), and unexplained weight loss also became unwelcome symptoms. Plus, I started to develop high anxiety when going anywhere or doing anything socially, due to my various symptoms.

Over a few months, these symptoms intensified. By the time I returned to the office in July, my double vision was so bad that driving felt too dangerous: a car would appear to be in front of me, when it was actually in the lane to the side. As such, I had to inform my employer that I could no longer drive to the office, which was a 100-mile round trip. I started to develop muscle weakness, particularly on the left side of my body– even lifting a kettle became a struggle. Several phone consultations with my doctor and subsequent blood tests yielded no answers, a frustrating reality during the peak of COVID-19, when seeing a GP was very challenging. Finally, a referral to a neurologist and the intention of an MRI within two weeks offered a glimmer of hope.

The final red flag occurred after a particularly taxing workday at home. I sat on the sofa and lost all feeling in my left arm and leg for a terrifying 20-30 minutes. This health scare prompted a trip to A&E the following morning, despite the anticipated long wait. After five hours, a nurse conducted basic tests and asked questions, but couldn’t pinpoint the problem. Another two hours in the waiting room led to a doctor seeing me. After a brief conversation and reflex tests, they suspected something wasn’t quite right, and agreed an MRI was necessary. In a stroke of luck amidst the pandemic’s delays, a last-minute cancellation meant I had the MRI scan just 45 minutes later.

Brain Tumour Diagnosis – A Life-Altering Revelation

After the MRI, I returned to the waiting room, excited that after 8 hours, I was about to head home. Thirty minutes later, a nurse asked if anyone was waiting for me. I said my mum was in the car, and despite assuring the nurse I was fine alone, she suggested Mum joined me. I was escorted to a small consultation room with three chairs, a small table, and a box of tissues. This was when I realised this was a severe situation.

The doctor delivered the news: they had found a “mass” on my brain. The specifics were unclear, but the urgency was not. I wouldn’t be going home; emergency medical attention was needed. From the small consultation room, I was moved to a private ward, connected to a multitude of machines, and monitored around the clock. My initial three-day hospital stay felt isolating due to COVID restrictions, increasing my stress and anxiety. Thankfully, the unwavering support of close friends and family provided a lifeline during those early, uncertain days. The news was heavy, and sharing it was a delicate process, confined to my inner circle. It’s a tough subject to discuss at the best of times, and during COVID, everyone was struggling.

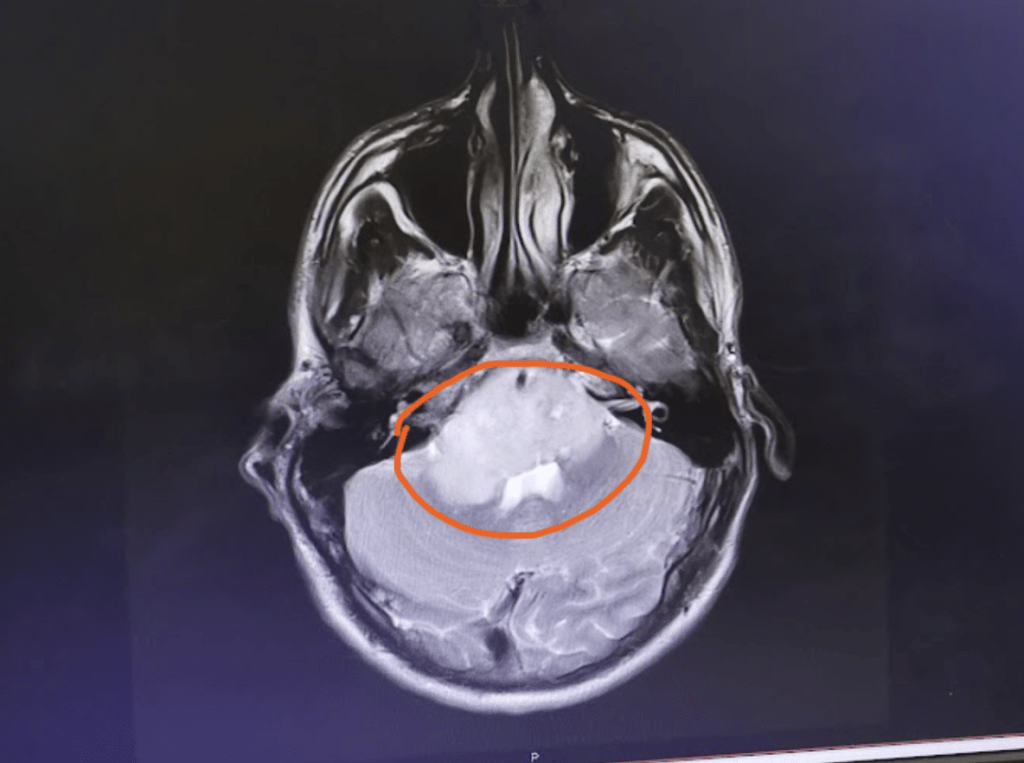

Once discharged from Chester Hospital, I received a call from the Walton Centre (formerly known as the Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery – a major neurology hospital located in Liverpool). I was told I’d be speaking with Dr. Brodbelt, a leading UK neurosurgeon, the next day. There, I was able to ask all my questions, was shown the scan for the first time, and in general had a lot of information presented to me – up till then, undisclosed.

The treatment options and severity of my diagnosis were also laid bare. I knew something wasn’t right, but I never expected it to be such a massive, life-changing diagnosis. Seeing the scan, the light grey mass dominating the image, showed how much of my brain has been taken over by the tumour.

Thankfully, I was assured it was treatable, and I was provided with a plethora of supporting information and groups I could reach out to for support. As is the case with any hospital referral, I was given the option to walk away and not receive further treatment, but I was advised that if I didn’t receive it, my best-case scenario was having 6 months left to live. Hearing this news caused a whirlwind of emotions – relief that it had been caught and could be treated, mixed with frustration at the diagnostic delays undoubtedly exacerbated by the pandemic. There was a strong possibility that earlier detection could have lessened the severity of my symptoms. Dealing with these mixed emotions is something I’d struggle with for the duration of my treatment.

Knowing that inaction wasn’t an option, I opted for a biopsy, followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The treatment plan we discussed covered an 18-month period, which included:

- A Brain Biopsy, a procedure to extract a small tissue sample for analysis. This involved a CT/MRI scan to pinpoint the tumour, followed by general anaesthesia (a preference based on past experiences). A metal frame was then fixed to my skull to ensure absolute stillness while a small hole was drilled, and a fine needle inserted to collect the crucial samples. To my surprise, the biopsy was booked for the day after I attended the initial meeting with Walton. (Due to the extreme situation, they’d decided it couldn’t be delayed) As this was less than a week since I first attended A&E, I didn’t have much time to process what was happening. I was terrified when I attended the hospital the following morning. I was taken to a room where, throughout the morning, 9 or 10 different specialists came to see me to explain who they were, what their role was in my operation, and to answer any questions. Although I was trying to keep a brave face, I was frightened – being on my own, about to go for major brain surgery, not knowing whether it would lead to a worse or better overall diagnosis (once the tumour sample had been analysed). I was taken down to the operating room, which was like something from a TV show. Being wheeled in is an experience I’ll never forget. The room was so bright, felt so clean, and the air was crisp. It was a huge room with a bed in the centre and equipment all around. I was surrounded by people, and before I knew it, I was asleep. I woke up and spent the next day in recovery, when I was under strict surveillance as I was struggling to speak, eat, drink and walk due to the invasive nature of the procedure. Thankfully, the following day, I was discharged in a wheelchair that I’d go on to use for the following few weeks. I was advised to take time to rest before starting the next phase of my treatment.

- Also known as radiation therapy, radiotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses radiation to kill cancer cells and shrink tumours. For my tumour, I received external radiotherapy, where a machine is used to carefully aim beams of radiation at the cancer. Once I had recovered enough strength to start the radiotherapy, I attended the Llan Clwyd Oncology Centre. Here, I met the team that would then carry out the remainder of my treatment. I was also told about the radiotherapy and chemotherapy I would be receiving, as they’d be my go-to for any issues or questions. 30 sessions of radiotherapy were scheduled over 6 weeks, Monday to Friday, with weekends for much-needed rest. Each session lasted 15-25 minutes, during which I was secured to a bed with a custom-moulded face mask to ensure absolute stillness. While the radiotherapy itself was painless, being strapped to a metal bed, having a mask so tight it was hard to blink or move at all, was incredibly uncomfortable and distressing. As the weeks progressed, the side effects became more pronounced: fatigue, nausea, hair loss, swelling, and difficulties with speech and concentration. The weight gain and bloating from medication further exacerbated the discomfort, making the mask feel increasingly restrictive and painful. Adding to the challenge were the strict COVID-19 hospital restrictions, which meant I often attended appointments alone, with my partner (now Wife) Hannah only allowed in the waiting room.

- Following radiotherapy, a four-week break allowed my body to recover before the most intense phase: Chemotherapy. To prepare for both treatments, I was advised it was essential to gain weight. With the help of a dietitian, I gained five stone (approx. 32kg) over three months. However, the high doses of dexamethasone steroids led to muscle degradation, significantly impacting my mobility. For over a year, a walking stick became a necessity, and for longer distances, a wheelchair was my only option. Chemotherapy, as anyone familiar with cancer treatment knows, is a horrible experience. My course involved daily tablets for 5 consecutive days, followed by a three-week recovery period, repeated for 12 months, allowing me to undergo treatment at home with monthly check-ups. My chemotherapy course began in late December 2020. Initially, the side effects were manageable, but by the end of the second month, a long list emerged: persistent nausea, uncontrollable numbness and tingling throughout my body, memory and concentration problems, constant fatigue, shortness of breath, constipation, and intense stomach pains.

A significant concern during chemotherapy was my severely weakened immune system, particularly during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Catching the virus was a serious threat, and concern. Chemotherapy also made me prone to cuts and bruises – a dangerous combination with my newfound clumsiness. Around halfway through the treatment, I got food poisoning – never a nice experience – but, given my poor immune system, I needed an ambulance to reach hospital, as my family had been unable to stabilise my condition, and I was continuously passing out.

It was also during this period that I faced a huge emotional hurdle. Until then, I hadn’t directly asked when my vision, balance and other functions might return to “normal.” The answer was a stark and painful truth: they wouldn’t. The tumour had already caused irreversible damage. Facing six more months of debilitating treatment with the knowledge that some side effects would be permanent led to severe depression, and weeks where I almost gave up hope entirely.

It was hard to find positives when the world was in a pandemic, my life had been completely turned upside down, and there was no clear finish line in sight. However, as all my family and friends were always there to support and reassure me, I was determined to do anything but give up. I took things one day at a time, not worrying or focusing on what the future would entail, or what hurdles I still needed to overcome. It didn’t matter that there was a marathon of obstacles ahead, I knew that if I just took it one step at a time, eventually I would reach the finish line. Given the nature of my tumour, I received MRI scans every 3 months for the first 18-24 months, and once the tumour appeared stable, the MRIs became every 6 months, and will continue indefinitely to make sure no more changes occur in my condition.

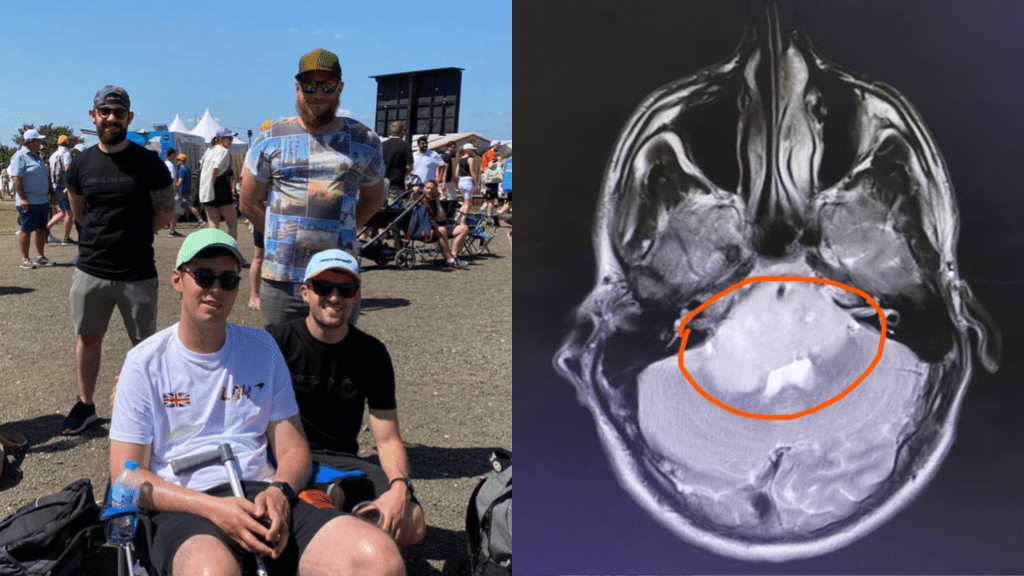

A significant morale boost arrived unexpectedly around three-quarters of the way through chemotherapy – a surprise trip to Silverstone for the F1. A lifelong fan, this was an incredible treat. Despite being very poorly, and relying on a walking stick, the experience was so exhilarating that it reignited my determination to finish treatment and strive for improvement. Navigating the crowds was difficult, but the joy of the event outweighed the challenges. I vowed to return to better health – a promise I’ve since kept, having attended twice more since that first visit.

Something else that helped me during my treatment journey was being surrounded by all the amazing staff. Without the constant reassurance, care and support from people in the NHS and various charities (Macmillan, Clic Sargent, Giddos Gift, Willow Foundation) throughout, I couldn’t have completed my treatment, and wouldn’t be where I am today.

Want more? Head over to Part 2: Moving Forward: Recovery, Community, and Finding Purpose