Introduction and overview

Over recent years, general awareness of mental health has undergone a radical change. Whilst there are complex drivers underpinning this social movement, the continuing need for us to go further and faster is stark: according to the World Health Organisation, mental health conditions now cause 1 in 5 years lived with disability and around 20% of the world’s children and adolescents have a mental health condition, with suicide the second leading cause of death among 15-29-year-olds (Source). As the charity Mind note, every single year, 1 in 4 people will experience a mental health problem of some kind (Source).

This article will begin to tell the story of how Newcastle’s outreach providers – HealthWORKS and Newcastle United Foundation – alongside the City Council and Health Diagnostics, have engaged in innovative work aimed at going further on mental health. This has been pursued by introducing assessments for common mental health problems into the NHS Health Check, which Newcastle’s teams carry out using Health Diagnostics’ digital solution: Health Options®. Whilst the findings shown below indicate that the NHS Health Check may indeed represent a valuable case-finding mechanism for both depression and anxiety, any such modifications to the National Programme are not without consequence. Based on the findings, over 10 minutes extra are required to conduct NHS Health Checks that contain a more in-depth mental health assessment. The article concludes with some recommendations for how the impacts identified in this trial may be mitigated.

The question of whether the NHS Health Check should include elements on mental health

Statistics such as those cited above led, in 2021, to Public Health England (PHE – now the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities) asking the question of whether the NHS Health Check may be a conducive way of identifying people at risk. Given the remit of the NHS Health Check – which is available once every five years to all 40-74 year olds who don’t already have diagnosis of a chronic condition – it reaches millions across England each year. Whilst the focus of the NHS Health Check has historically been on CVD prevention, the programme provides an almost unrivalled opportunity to engage people on their health and wellbeing more generally.

Despite this potential, there are numerous considerations to work-through before any such introduction of elements relating to mental health. To note but a few:

- What assessments could be used to efficiently assess common mental health problems such as depression and anxiety?

- How would introducing any such assessments affect the delivery of an NHS Health Check, both in terms of time taken and the competencies required to deliver?

- What should be the next steps if someone is identified as being at risk?

- How do people experience being asked questions on their mental health in a consultation that’s otherwise focused on CVD prevention?

- How effective is the NHS Health Check as a case-finding mechanism for common mental health problems?

It’s questions such as these that led PHE to establish a Task and Finish Group – a consultation network of independent specialists working in relevant domains – to provide expert feedback on the sorts of points highlighted above. Alongside individuals from local and central government, academia, and NHS mental health services, a representative from Health Diagnostics contributed to the Group on questions regarding technological feasibility.

Amongst those to feed in from local government was Lynda Seery, Public Health Specialist from Newcastle City Council, with whom Health Diagnostics have worked closely for numerous years. Given the urgent questions that emerged from the Group, Newcastle City Council, with the support of Health Diagnostics, decided to gather some real-world evidence by trialling the proposals on the ground. The remainder of this article covers some of the key outcomes established from this work.

Trialling mental health questions as part of the NHS Health Check in Newcastle

A range of engaged community providers have constituted an integral part of Newcastle’s NHS Health Check delivery network for a number of years; specifically, HealthWORKS and Newcastle United Foundation. Health Diagnostics have long-standing relationships with these community outreach teams, having provided them with a complete digital solution for delivering health checks in all manner of outreach settings.

Crucially, through the process of collaborating, it emerged that HealthWORKS and Newcastle United Foundation were particularly well-suited to the mental health project due to their natural familiarity with providing such support. As members of these teams explained, having conversations relating to mental health are often a natural part of supporting the people and communities that they do.

Having identified the ideal providers to spearhead this work in Newcastle, the following was undertaken:

- Health Diagnostics updated the configuration of the digital solution used by HealthWORKS and Newcastle United Foundation to incorporate the assessments recommended to the Task & Finish Group. These were:

- For depression: Two initial Whooley questions. If a trigger threshold were to be reached, the nine questions of the PHQ-9 to be asked

- For anxiety: Two initial GAD-2 questions. If a trigger threshold were to be reached, the seven questions of the GAD-7 to be asked

- Specialists in CVD prevention and mental health trained Newcastle’s teams on asking these questions using updated version of Health Options and advising on next steps; key ‘before and after’ training outcomes are shown in Fig 1

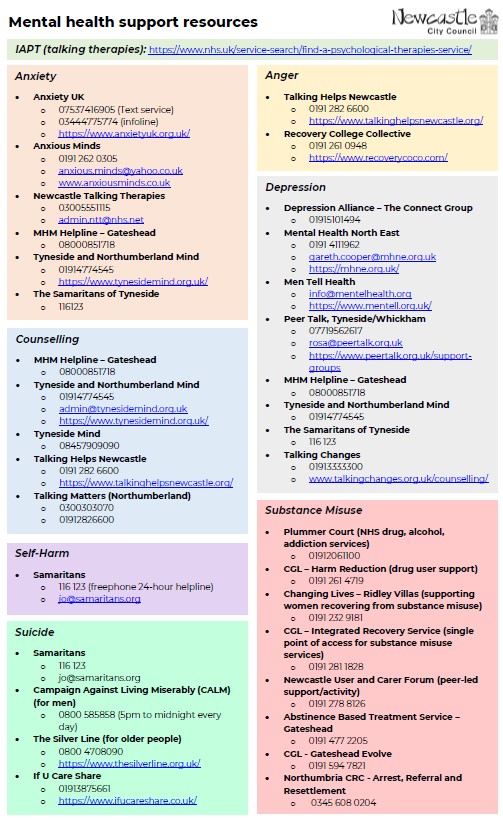

- Representatives from HealthWORKS, Newcastle United Foundation, and Health Diagnostics worked together to establish and produce a range of mental health signposting and referral resources (see Fig 2)

- HealthWORKS and Newcastle United Foundation began delivering NHS and workplace health checks that routinely incorporated mental health assessments

Analysis

The content below details the initial findings from the first four months of Newcastle’s teams delivering the updated health check. These figures relate to ~160 unique assessments, all of which included components on mental health and were conducted by either representatives from HealthWORKS or Newcastle United Foundation.

Depression assessments

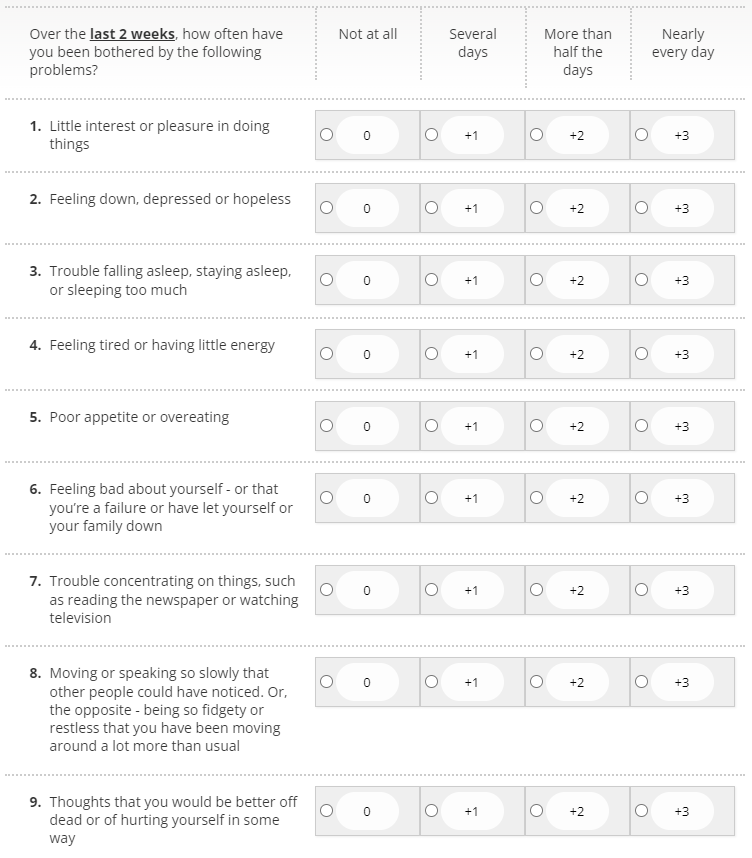

39.5% of people that were asked the initial two Whooley questions were eligible to be asked the full PHQ-9 (see Fig 3 for PHQ-9 questions).

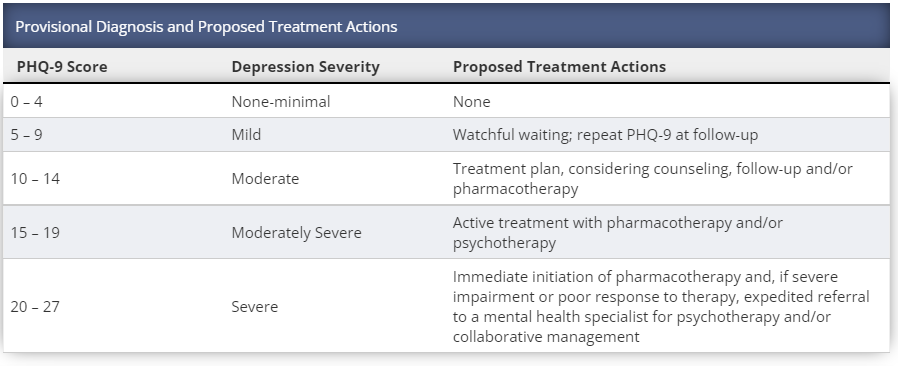

Overall outcomes collected from those that were asked the full PHQ-9 depression assessments were as follows:

- No-minimal depression = 75%

- Mild = 6.3%

- Moderate = 9.4%

- Moderately severe = 6.3%

- Severe = 3.1%

Crucially, 7.4% of all people asked questions about depression (including Whooley and/or PHQ-9) would be eligible for follow-up treatment of varying kinds, with psychotherapy potentially clinically indicated for 3.7% (see Fig 4). On the face of it, these figures are slightly elevated above the number of people that Mind suggest will have a specific diagnosis of depression in any given week in England: 3 in every 100 (Source). Admittedly however, the clinical thresholds used across these varying sets of statistics may differ.

Anxiety assessments

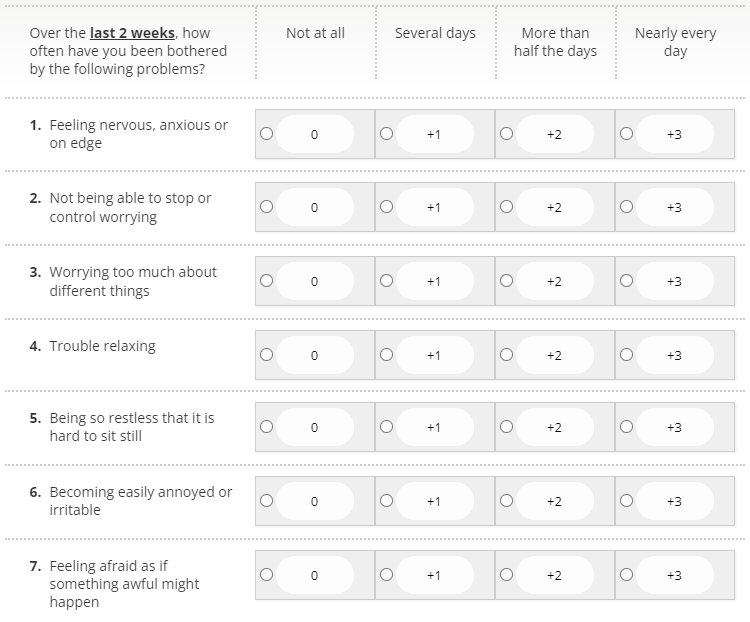

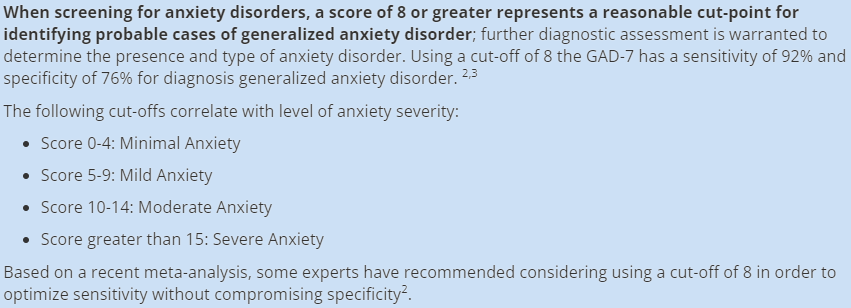

12.8% of people that were asked the GAD-2 questions were eligible to trigger the full GAD-7 (see Fig 5 for GAD-7 questions).

The outcomes from the full GAD-7 anxiety assessment were as follows:

- Minimum anxiety = 90.2%

- Mild = 5.5%

- Moderate = 1.8%

- Severe = 2.5%

Based on the research, 6.1% of people that were asked questions about their anxiety (including GAD-2 and/or GAD-7) would be potential candidates for a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder (see Fig 6). Interestingly, this aligns precisely with the number of people that Mind state qualify for a specific diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) in any given week in England: 6 in 100 (Source).

Timings and feasibility

Consultation timings were as follows for the different types of health check delivered:

- HCs before the addition of the mental health questions: 22:48 mins (baseline)

- HCs where only the two Whooley and two GAD-2 questions were asked: 23:05 mins (+17 secs)

- HCs where all mental health questions were asked (i.e. where the Whooley and GAD-2 questions triggered the full PHQ-9 and GAD-7): 33:13 mins (+10:25 mins over baseline; 10:08 mins over 2 MH Qs)

In summary, asking only the Whooley and GAD-2 questionnaires extended these consultations by, on average, 17 seconds. Given the time pressures on NHS Health Check providers, timings of this order arguably maintain feasibility.

However, where the full mental assessments (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) were asked, consultations were extended by, on average, >10 mins. Such an extension is likely due to the sensitive nature of some of the questions contained within those full assessments, affirmative answers to which invariably necessitate further investigation (e.g. Q.9 on the PHQ-9: “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you had thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?”)

Patient experience

In addition to the questionnaires, two further questions were posed to ascertain how people felt about being asked about their mental health. These were as follows, with the outcomes detailed below the respective questions:

- How important do you think it was that questions on mental health were included as part of your NHS Health Check?

- Very important = 59.0%

- Quite important = 28.6%

- Neither important/unimportant = 3.1%

- Quite unimportant = 2.5%

- Very unimportant = 6.8%

- How effective at capturing your recent mood were the mental health questions that you were asked?

- Very effective = 48.5%

- Quite effective = 40.5%

- Neither effective/ineffective = 6.1%

- Quite ineffective = 0.6%

- Very ineffective = 4.3%

As these data show, a significant majority (87.6%) of people that were asked questions about their mental health felt they were either quite or very important elements in their consultation. A similar proportion (89%) felt that the questions were either quite or very effective at capturing their recent mood.

Conclusions and recommendations

For and against

Given the statistics presented above, the NHS Health Check clearly presents an opportunity to identify people that are at risk of experiencing common mental health problems, with the numbers identified via this route broadly representative (if not slightly in excess of) of the proportion of people in the population known to be at risk of conditions such as depression and anxiety (Source). From a patient experience perspective, these questions appear to represent a valued addition to the consultation.

These arguments in favour are echoed and advanced by those delivering the programme; according to Ellen Bullock, Health and Wellbeing Project Officer at Newcastle United Foundation, “I think the mental health questions have been a great addition to NHS Health Checks and helped to open conversations about mental health and wellbeing. They are absolutely needed both in terms of checking people’s mental health but also in terms of education and stigma reduction. There were undoubtedly individuals who became aware of potentially having a mental illness due to having an NHS Health Check.”

Ellen goes on to describe an instance where she felt these checks really allowed her to reach someone: “I saw a woman who at the start of the check did not know anything about mental health, however her answers to the GAD7 suggested she may have anxiety. This opened a conversation about mental health and mental illness, what anxiety is, how it can affect people, how mental illnesses are treated, and how to access professional support for her mental health. To help reassure her I opened-up about my experience of having anxiety and the treatment I went through, which she thanked me for and said it had helped convince her to go see her GP.”

Whilst Ellen and colleagues have clearly been able to make real contact with people, in part through taking such an open and engaged approach, it remains the case that any clinical benefit must be balanced with feasibility. As anyone involved in the NHS Health Check Programme and primary care will know, GP practice staff – the professionals that deliver the majority of health checks nationally – are already under significant pressure. The prospect of adding a further 10 minutes to the health checks that these practitioners deliver is unlikely to be a viable prospect given the current conditions and funding arrangements.

Crucially, because not all individuals will trigger the full mental health assessments, uncertainty is introduced as to who may and may not require the additional time. Moreover, there is a further question around training needs: as it is predominantly healthcare assistants that deliver NHS Health Checks within GP practices, confidence around enquiring about mental health may be lower than amongst other health professionals, such as GPs themselves.

A possible way forward

The first of these issues – the question of who may need the additional time – is something that may be addressed using the latest developments in Health Diagnostics’ technology: the digital self-assessment component of Health Options CS (see Fig 7). This tool enables a range of initial questions to be asked via our digital platform in advance of the health check. If the Whooley and GAD-2 questionnaires were conducted by self-assessment initially, the outcomes could be used to triage the cohort, thereby enabling those that trigger the full GAD-7 and/or PHQ-9 assessments to be allocated a longer consultation.

Given the fact that the full GAD-7 and PHQ-9 involve sensitive questions that may require immediate follow-up if affirmative answers are given (see Figs 3 and 5), Health Diagnostics would not, from a clinical risk perspective, recommend asking these questions via self-assessment. In our view, it would be prudent to ensure the containing presence of a health professional when broaching such topics.

Training is a further systemic consideration. As shown by Fig 1, even practitioners that frequently find themselves providing mental health support are not always confident in how to have such conversations. As those same training outcomes demonstrate however, a coherent and targeted training programme can significantly boost this confidence. Based on the outcomes cited in Fig 1, there is every reason to suggest that, even if health professionals initially feel uncertain about enquiring into depression and anxiety, they can quickly get to a stage where they are both prepared and competent. Further CPD, such as free training provided by the Zero Suicide Alliance, is also strongly recommended, if not essential (Source).

In summary, the findings from this small trial suggest that the addition of questions around mental health may represent a valuable addition to the NHS Health Check, providing the resources and competencies are in place locally. Whilst there would no doubt be challenges to rolling any such modifications out on a national scale, doing so with the support of effective digital technologies that, first and foremost, keep the patient and provider in focus, is likely to prove a defining factor for success.