Whilst it’s widely acknowledged that women tend to live longer than their male counterparts (latest UK life expectancy data puts the female average at 82.9 years and the male average at 79.3 years), what is less well known are the startling premature mortality figures that are contributing to this gender gap. According to the Men’s Health Forum, a significant proportion of males are falling decades short of this national average, with one man in five dying before he even reaches the age of 65.

With this week (13th – 19th June) having been Men’s Health Week, we at Health Diagnostics thought we’d take the opportunity to reflect on some of the issues surrounding male health as they’ve presented themselves to us in our preventive health work. Despite the majority of this work being dedicated to supporting NHS Health Check projects around the country (and therefore predominantly concerned with improving the nation’s cardiovascular health), there is an undeniable interface between physical and mental health that means any discussion of this type would only be half complete if it were to ignore the mind and only take account of the body.

As it states on the NHS Choices website, a person’s gender plays a key role in their risk of developing cardiovascular disease, with men being “more likely to develop CVD at an earlier age than women”. Amongst the overarching reasons for this is the fact that, as studies into human evolutionary psychology have found, “males are more likely to take risks than females… [and] risk taking is a pervasive feature of human male psychology”. In the context of cardiovascular disease, this tendency contributes to higher rates of some of the key risk factors amongst males; men are more likely than women to drink alcohol above recommended levels, smoke cigarettes and eat a poor diet.

Moreover, this prevalence of risk factors is exacerbated by the fact that males access primary care services far less than females, with men visiting a GP on average 20% less than women. Crucially, men also take longer to present and receive a diagnosis. As a result, when it comes to preventing poor health and non-communicable disease, male populations can often prove to be amongst the hardest to reach groups.

The phrase ‘hard to reach’ however, in the context of male health, is often tinged with another meaning. In addition to the challenges associated with persuading men to access primary care services before preventable illnesses require treatment, encouraging men to open up about their mental wellbeing is also an area where more desperately needs to be done. As Grayson Perry examined in his recent television documentary entitled ‘All man’, ‘reaching’ males in this sense may be difficult for a variety of social and psychological reasons, many of which arguably revolve around an unwillingness to show weakness. The bottom line however is that all too frequently, internal pressures remain unspoken and tragic consequences ensue. The fact that the suicide rate amongst middle-aged men is now at the highest rate it’s been since 1981 and is on the rise, demonstrates the fatal effects that too often result from men feeling emotionally out of reach.

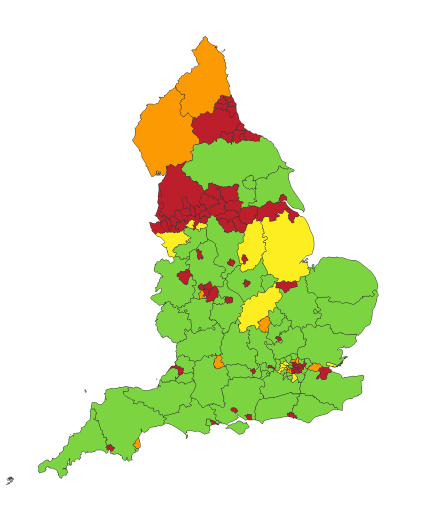

Far from impacting men equally across the UK, the ‘silent epidemic’ of suicide affects 75% more people in the North East of England than it does in London, for example. What’s more, equally profound cardiovascular health inequalities pervade the UK. Amongst the key questions that therefore need addressing is: what are the causes of these disparities in mental and physical health and why is geography regularly such a prominent factor? With epidemiologists and others dedicating huge efforts towards understanding multi-factorial questions such as this, a meaningful answer requires more elaboration than can reasonably be achieved in a blog post. However, something that appears to surface time and again is the issue of expectations; those that society currently place on men, the (potentially different) expectations that society has historically placed on men, and those that men place on themselves.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that the North East of England – an area that’s proud industrial heritage has experienced terminal decline over recent decades – has some of the worst premature mortality rates in the country and the highest number of suicides among all England’s regions. (ONS) As Whitby et al cover in their 1999 study on The Rural Economy of the North East of England, with the decline of heavy industry in the mid 1970’s came a sharp rise unemployment, particularly amongst men that were highly skilled in areas increasingly deemed redundant.

Despite the rapidly changing economic conditions however, you could argue that longstanding attitudes around gender identity – around being a ‘hard man’ as Grayson Perry’s documentary put it – have been less inclined to change. You could also argue that the emerging lack of industrial jobs has made any such ‘physically demanding’ expectations increasingly difficult to fulfil. There are arguably few places where this discrepancy between traditional expectations and current economic reality is more pronounced than in the North East.

Whilst some might say adaption is what’s required, change can be hard and the prospect of reconfiguring identity is anxiety-inducing. This is no doubt particularly the case if there’s also a feeling of falling short of previous generations. What’s more, when the norm is to not show fear – perhaps not even to yourself – anxiety is offered no outlet and the only place left for it to go is underground. As is uncompromisingly quoted by Tim Jonze in his piece for the Guardian on the subject, “often men don’t even realise they’re sad… boys are brought up to unconsciously feel they would be breaking their man contract if they were to cry too much. That’s why men kill themselves – they bottle up, bottle up, bottle up, bottle up, until they’re overwhelmed by it.”

So what can be done? It would be disingenuous to suggest that entrenched attitudes are simple and swift to change. What would no doubt help the process however would be if men, en masse, felt able to open to others and themselves about what’s going on inside of them. Moreover, as has independently been shown to be the case, the positive effects of doing so would likely span the mind-body divide; according to the research, increased self-awareness and improved mindfulness can have a direct impact on physical health.

Perhaps one of the most crucial changes however may already be underway. It’s the shift that this article and many thousands of others like it are tapping into; the fact that issues around men’s physical and mental health can no longer be swept under the carpet. The conversation has started and with headlines such as “Traditional male role weighing heavy” starting to appear in mainstream news outlets, momentum is undoubtedly building. As is so often the case for both individual and social change, realising there’s a problem that’ll need to be tackled in a thoughtful way represents a vital first step in a new direction. Despite the difficulty involved, there are strong indications that this significant first step is being taken.